Halifax founders under provincial tax CAP

No one knows how property taxes work

By Matt Stickland

At last Tuesday’s council meeting, councillor Janet Steele started trying to fix a generational mistake.

Back in the early 2000s, like today, people didn’t like paying property taxes. And back in the early 2000s, just like during COVID, people with Ontario money started buying property in Nova Scotia. This leads to an issue where property values go up on run-down family homes due to million-dollar homes being built next door. Or at least it leads to the perception of this issue.

According to a 2004 Provincial Communications Plan, the influx of Ontario money led to “the image of ‘the little old lady’ being taxed out of her humble home,” which “has become the stuff of Nova Scotia media myth.”

It’s a myth because that’s not how municipal taxation or property taxes work. Unlike the feds or provinces, whose tax revenues are determined by what they collect, the city’s tax rate is the reverse: it’s set based on the cost of municipal expenses. Meaning if the city had $10 worth of expenses and you and your neighbour both had homes assessed at the same value, you’d both pay $5 in taxes. But if your home were valued at one-tenth the cost of the million-dollar home next door, then you’d pay $1 in taxes while your neighbour paid $9 to cover your city’s $10 worth of expenses. Unequal property tax splits are the reason Steele is digging into the topic. These are caused by the province’s Capped Assessment Program, which limits how much a home’s assessed value can increase year over year, 1.5% this year. As people stay in their homes the CAP keeps their assessment and therefore tax rate low, they start paying less tax than their new neighbours whose homes reset to a higher starting value and who pay more for the same city services. Both groups demand property taxes stay low and not keep pace with inflation or their home’s value.

But cities needed more revenue because Nova Scotia’s single-family home development patterns are wildly unsustainable. So as property assessments went up, cash-starved municipalities kept spending the same or more, but assessment values going up kept masking cities’ underlying unsustainability.

From 2020 to 2030, Halifax has averaged and is expected to continue averaging annual budgets of around $1 billion, which is the $10 in our two-house city analogy. During this same decade, the city will have borrowed about $1.8 billion by 2030. This is to cover the costs of upgrading infrastructure to accommodate growth and to finally fix infrastructure built in the 1970s (the maintenance of which has largely been deferred). This is equivalent to $18 in our two-house city. Or, in other words, if Halifax is our two-house city, even though we’ve been paying $10 a year for city services and infrastructure, our city spent (and needs to continue spending) about $12 a year from 2020 to 2030. And even though people like city services, they don’t understand how their taxes pay for them.

This problem exists today as it did in the early 2000s, so when property taxes started going up, city councillors started throwing the province under the bus, blaming it for the high property taxes required to fund their politically popular but fiscally catastrophic municipal land-use bylaws.

The provincial government had very little time for the city’s bellyaching because cities set their tax rates by approving spending and decide for themselves how heavily to rely on property tax as revenue. And as a different 2004 Provincial Comms Plan notes: cities have “made considerable efforts to scuttle every attempt by the province to resolve the issue. The bottom line for municipalities is that they are opposed to any solution that will cost them a dollar in revenue.” This plan also notes that cities could lower people’s property taxes through a different legal mechanism known as deferral, but didn’t “even though they already have that authority under the Municipal Government Act.” The plan also noted that “a CAP set too low will antagonize municipalities.”

Cities were asking for property values to be allowed to increase by 25% a year before the CAP kicked in. According to a 2004 provincial report about the potential impacts of the cap, in 2005 only 854 properties out of the HRM’s total 130,078 would hit a 25% CAP, and the difference between those 854 capped and 110,872 uncapped property tax bills would be about $105 on average. But if the CAP had been set to inflation (2-4% instead of 25% like the cities wanted), 89,694 properties would have qualified in 2005, and the difference in value between capped and uncapped property tax bills would be $140. The report went on to say that, if the province set the CAP to inflation, by 2007 the difference between a capped owner and a new homeowner’s tax bill in Bedford would be $770. Or, in other words, people who moved to Bedford in 2007 paid 33% more in property taxes than existing Bedford residents for the same homes and the same municipal services.

Capping the value of low-density residential properties does not change how much money cities need to spend; it just changes who pays for it.

Let’s check in on our $10 two-house city, with one house paying $1 and the other paying $9. The city’s expenses have risen with inflation, so it now needs $10.20 in property taxes. But both households also had a baby, so they need a new park, and that’s gonna be another $2. And the roads need to be repaired faster than we anticipated, so that’s gonna be another $2. So this year we need $14.20 in taxes. Now, as long as neither property is resold, the split stays the same with growth, and the $1 bill becomes $1.42 and the $9 bill becomes $12.78. This all changes if one house changes hands, because when a house changes owners, the property tax CAP resets to the current market value of the house. Which in this case would mean that if the lower-value home sells, the CAP resets and both houses pay closer to $7 in taxes. But if the more expensive house sells and that CAP resets instead, that property would take on even more of the share of the city’s tax burden, while the other one would pay even less than its projected $1.42.

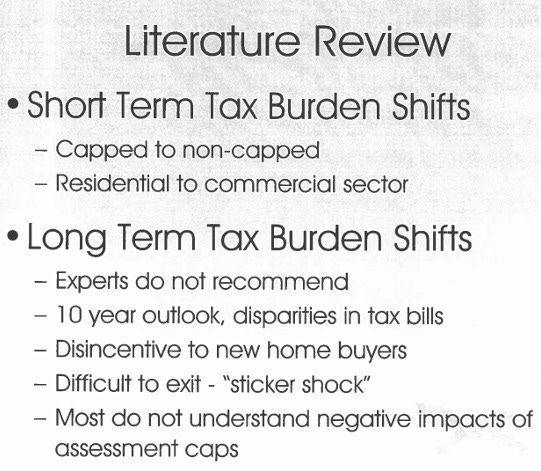

Councillor Steele is concerned that when young families buy their first home they have to pay the current assessed value, whereas their nextdoor neighbour’s home gets assessed like it’s still 2007. Speaking of that year, in a 2007 provincial staff presentation to an Executive Council Issue Committee meeting the presentation’s slide deck says that with a property tax cap, in the short term, the tax burden would switch to non-capped properties, like apartments, and from residential properties to commercial ones. In the long-term burden section, the headings are things like: “Disincentive to new home buyers” and “most do not understand negative impacts of assessment caps” and “experts do not recommend.” But all of these long-term consequences were fine because a CAP “may help some on fixed or low income.”

But helping people on fixed incomes is not and was never a part of what the CAP was supposed to achieve. In a 2004 provincial “REGULATION (RED TAPE REDUCTION) CRITERIA CHECK LIST” the deputy minister notes that the CAP legislation was to prevent “large increases in assessment,” and its success would be judged by “property owner satisfaction.”

One of the predicted consequences of the CAP was that homeowners would be incentivized to stay in capped homes. This, combined with low-density land-use bylaws and the federal government not building public housing, led to a scarcity of property, which drove up its value. At the same time, the government’s lack of public housing spending opened the door for private housing development. Low-density land use, lack of public investment, and, in Nova Scotia, the property tax cap, led to a massive increase in artificial scarcity of residential property. This scarcity led to high demand and the associated higher prices.

At the same time, other factors affected housing, like middle-class citizens in countries with restricted financial markets investing in Canadian property. Internationally, Canadian real estate is seen as an excellent investment with its high demand and low supply making it a good financial market to grow wealth.

More buyers for a scarce supply drove up demand and prices. In the mid-2020s things got worse due to the lack of housing supply and high investor demand for residential properties. And high demand for residential properties from people who want to sleep indoors. And made worse still by policies from the federal government to give first-time home buyers access to more debt to compete with institutional investors has led to yet another massive spike in property values. Meanwhile, wages have not gone up at the rate of home prices. And at the same time, real estate makes up about one-fifth of the Canadian economy. When combined with Canada’s general fiscal unsustainability at the individual and institutional levels, a drop in property values is game over for the economy.

As Halifax’s 2009 Tax Reform Committee found in their report, property taxes aren’t and haven’t ever been equitable. It is indeed a tax based on an asset, and assets are often proxies for wealth, but in today’s market, living in a $1 million home is more likely to be an indicator of a new family in a lot of debt than a rich person who can afford to pay taxes on a $1 million asset.

Or, in our two house $10 turned $14.20 city, the more established property owner who bought decades ago has a capped property, and his taxable home value can’t go up by more than inflation. But the family that just took out a million-dollar mortgage to get into their home? Their CAP shot up to the new $1 million market value. Even though the long-time owner was only going to pay $1.42 of that $14, he’s now going to pay way less. Even though the new home buyer is paying almost 10 times more for the new park and road, both residents get the exact same thing.

The report that councillor Janet Steele asked for will provide a much more detailed explanation of this very short history of Halifax’s tax inequity. The report will be included when the city sends a letter to the province asking for changes to the property tax cap, which is currently most punishing to immigrants, seniors looking to downsize, young middle-class families trying to buy their first investment property, and renters.

Wanna read that FOIPOP for yourself?

Fill yer boots

The Other Stuff

There’s a podcast; this week, the episode is not for everyone, but it does recap what went down in standing committees last week. Show notes will come later in the week. The Moosehead’s opponent got a flat tire on the way to the minor hockey game on Sunday, which really jammed up my publishing schedule.

Here’s the digital issue of the paper for your at-home crossword needs.

How did you do on last week’s puzzle? Find out below.