The Savage austerity trap: Halifax’s decade of decline

Why doesn’t council value Haligonians?

By Deny Sullivan

Halifax, like most municipal governments, takes pride in being the level of government closest to people’s daily life—whether that’s calling 311 for a pothole or contacting their councillor about the same pothole.

In return, the HRM has told us we’re not worth helping; the improvements in our city are simply not worth the cost. Desperately needed transit expansions get delayed for years and are still years away. Library workers can’t get a living wage. Stalled projects like re-working the Windsor Street Exchange become more difficult, more costly, and further away from council’s stated priorities.

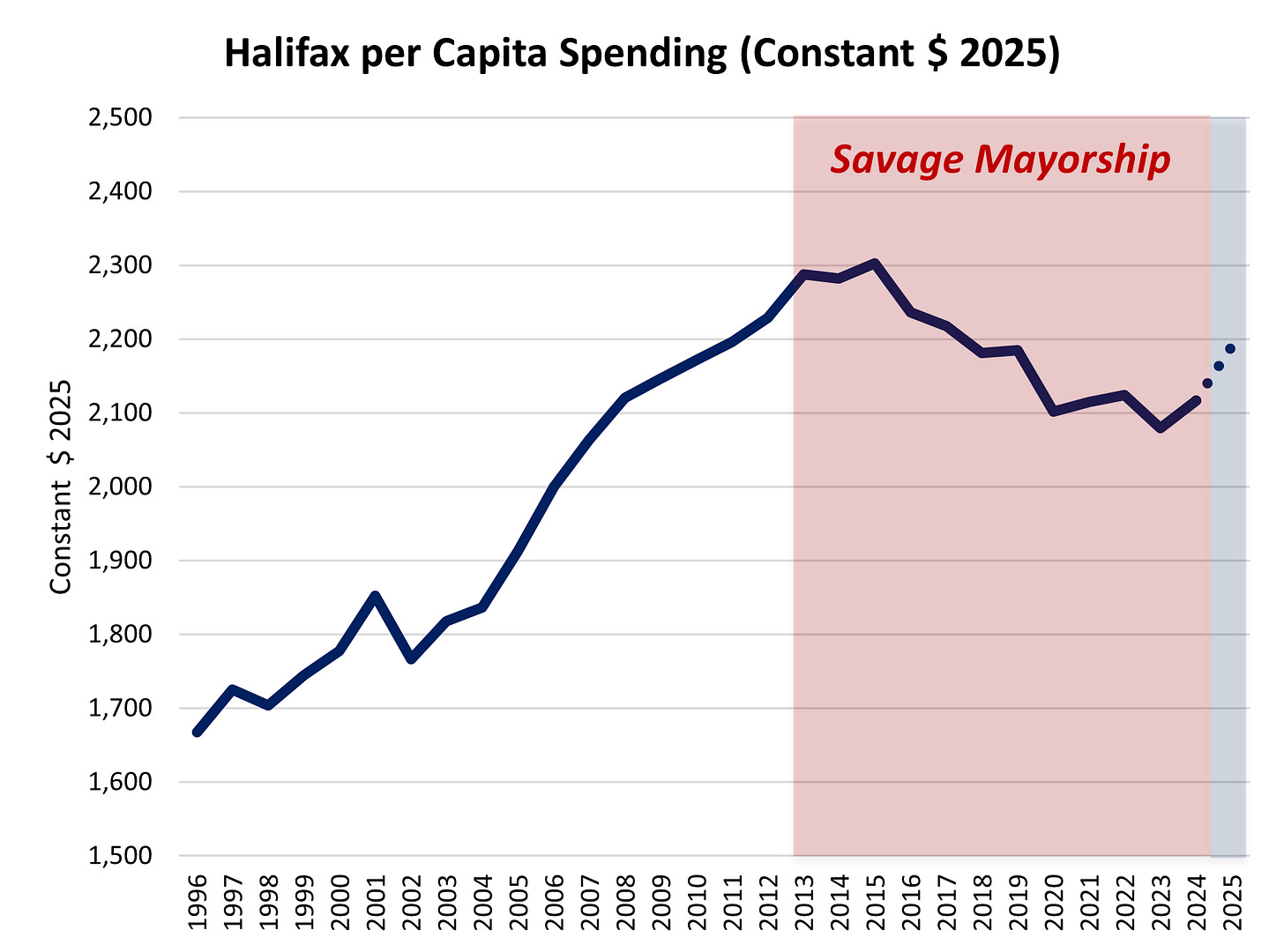

The dependence on property taxes raises the importance of using that tool to properly fund HRM services instead of complaining while letting municipal services decline. The evidence is clear on this front: Halifax’s councillors have spent 12 years choosing austerity over growth.

While the municipal budget has grown by about 4% per year since 2012, this growth has lagged the combination of inflation and population growth. After inflation, HRM spends fewer dollars per resident than it did 12 years ago. The austerity from Grand Parade means cancelled ferries, unreliable buses and thousands more potholes—with less money to fix any of it.

The dominant cause of our flailing municipal government is a lack of funds, which comes from a fear of raising property taxes. Councillors are elected with low turnout. Municipal voters trend older and more likely to be homeowners in a context where few voters are paying attention, keeping property tax bills low dominates re-election concerns.

In Nova Scotia, a council that passes an austerity budget further punishes its residents thanks to the provincial Capped Assessment Program (CAP). The CAP overrides assessments for 1-4 unit properties to limit the increase to Nova Scotia’s inflation rate. This sows confusion among voters about their tax bill. In this year’s budget cycle, CBC had headlines like:

“Halifax to keep property tax rate flat, bills going up about 4.7%”

But for 90% of homeowners with the CAP, their tax bill will only go up by 1.5%, the general inflation rate last year.

The difference between 4.7% and 1.5% is about $10 per month.

HRM makes up that 3.2% difference through new growth and CAP’d assessments resets. When a property is sold, the CAP resets, increasing by an average by 60%. As councillors fret a 1.5% tax bill increase, first time homebuyers punished with 60% increases in taxes to make up that 3.2%. If this council wants more austerity, so be it, but will push more and more of the city’s costs onto young families already struggling from the housing crisis.

From 2012 to 2024, while inflation-adjusted spending per person has fallen for HRM, both the province and the federal government have significantly increased spending (+20% provincially and +24% federally). There is a sad irony that the municipal government, which invests directly in improving your daily life, has decided to invest so little in Haligonians. For context, if Halifax had just kept pace with the provincial government, it would have an additional $275 million in this year’s budget. That’s about enough to double the Halifax Transit and Halifax Police budgets.

Halifax doesn’t lack financial tools; it lacks political will. Mayor Andy Fillmore campaigned to keep the tax rate flat and spent his time during the budget process trying to find even more cuts after a decade of decline. That included pillaging reserve funds for the central library. At some point, our council must accept their duty to fund services. As our councillors, quoting a former U.S. President, often say, “Don’t tell me what you value, show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value.” The evidence is in, for the past 12 years council didn’t value Haligonians.

Police Commissioners slack off

By Matt Stickland

Halifax’s Board of Police Commissioners was supposed to meet on Wednesday, May 7, but this was cancelled due to lack of quorum.

When the Boards schedule was set in November 2024, staff told the commissioners that only six meetings were needed in 2025. It’s enough to meet the minimum requirements of provincial legislation, and the 15 reports coming to the board this year can easily be handled in six five-hour meetings. So far in 2025, two meetings have been cancelled, and one ended early. As currently scheduled, it’s unlikely the remaining reports get more than one hour of public scrutiny.

Had the board met, they would have learned that Halifax is top five nationally for hate crimes per capita, behind Kitchener, Peterborough, Kingston, and Gatineau (just the Ontario part). They may have discussed what they or the police could do about the rise in hate. They may have noticed and debated that the RCMP’s hate crimes investigation guidebook says that a “critical role” the police play in hate crimes is that of a social worker.

They may have debated the police’s policy on the armoured personnel carrier. We don’t have the APC yet; we’re scheduled to buy it on May 20. For a few weeks, the police may have a new toy that can be a weapon with no board-approved policies on its use.

The board was supposed to adopt a policy to improve police communications in and after events like the mass shooting of 2020 or the unhoused eviction of 2021. However, the Matters of Immediate Strategic Significance (Critical Point) report must wait until next meeting.

In 2021 the Board instructed police to start doing an automatic case review if a sexual assault complaint didn’t go to trial to find out why. The police have instead begun doing an RCMP-led case review round table for sexual assault cases that the police select for review. Comissioner Tony Mancini was going to ask the RCMP to write a report about the “performance and findings” of this round table. Mancini may ask for this report—which has no glaringly obvious real or perceived conflicts of interest—at the next meeting.

The recently approved extra-duty policy was not in line with provincial regulations, so the board must wait a month to correct this mistake.

The board was also supposed to send a report detailing all the work they did last year. In the report board members say they could be better at sticking to priorites and they should be more involved in police strategic planning

This meeting may be rescheduled to late May.

Why does Halifax plan to fail?

By Matt Stickland

On a recent Atlantic News podcast, city councillor Laura White said that the city has known since 2006 that car-centric planning is a huge issue, and fixing this issue is slow

But slow implies progress is being made when it’s more accurate to say Halifax is preventing itself from succeeding.

It’s obvious stuff, like the massive expense of car infrastructure. Robie Street is being widened for at least $150 million just to maintain 900m of car traffic in a bus transit corridor. And it’s less obvious stuff, like 2013 when the city of Halifax commissioned a report and found it costs Halifax twice as much to service a suburban home as one downtown. With higher assessment values and density, Downtown homes cost the city way less to service and generates most of the city’s revenue.

In addition, most, if not all, of Halifax’s strategic plans recognize the issues with automotive infrastructure. In addition to the massive cost to build and maintain roads and the decreased municipal revenues it also causes hostile climate changes and violent health outcomes for the people of Halifax.

This is likely why, early in her tenure, Halifax’s chief administrative officer Cathie O’Toole, told councillors that automotive infrastructure was such a huge cost that the city would need to “rationalize” its use of roads in answering questions at a council meeting.

Despite this, when the city updated its municipal service catalogue late last year, it included instructionsto staff to accommodate all modes of travel. Which seems innocuous except for the fact that multiple strategic plans, multiple studies, the city’s budget and the laws of physics all say that accommodating car traffic will result in more car traffic and all the negatives consequences the city is trying to prevent. So how is it possible with all of this evidence explaining in one way or another that it is impossible to accommodate cars without cars inadvertently becoming the priority and that automotive accommodation is, more or less, the foundation of most of our city’s issues? How did no one notice the reams of municipally generated evidence showing that our core service delivery standards are fundamentally self-defeating?

What Happened Last Week:

Monday

Nothing

Tuesday

Nothing

Wednesday

The Board of Police Commissioners meeting was cancelled.

Thursday

The Appeals Standing Committee had a meeting to discuss a property in Timberlea. The report says there are rocks and driftwood all over the property and Google Street View shows a property landscaped with driftwood and rocks. The property owner says it’s art, the city says it’s a hazard. The owner agreed to clean up the yard and was going to be granted extra time, but let it slip during the debate that clean up would be no issue. The committee subsequently voted against giving the owner additional time.

The African Decent Advisory Committee got a presentation from the new Department of Public Safety. This presentation included a brief history of the department, and even though the work to start this department was officially started by former mayor Peter Kelly, the work to start this new Department of Public Safety didn’t really start until former mayor Mike Savage took over and put this work in the office of the Chief Administrative Officer. This committee will also ask Halifax Water to make a presentation in the future so Halifax Water can explain how and why they feel it’s appropriate to jack up rates.

Friday

Did you miss what happened the week before last? Catch up on the go with our city hall podcast.

Doing the crossword at home? Here’s the paper for your printer.

How’d you make out in the crossword? Here are the answers to last week’s puzzle.